|

| (Source) |

Following the recent release of Kubo and the Two Strings (which I haven't had the chance to see yet, but which will probably get its own mention in a post eventually) I thought it would be a good time to talk a bit about the studio behind some of my most beloved animated productions. I'd like to look back on Laika's three previous major releases (Coraline, ParaNorman and The Boxtrolls), and maybe the potential comparisons between them. In all three films, to some extent or another, there's some underlying message about not judging by appearances, usually presented in a fresh or subversive enough way that we don't feel we're being beaten over the head by it, or that the young target demographic are being talked down to. The characters we may be initially inclined to view as monsters are often revealed to be more complex or misunderstood, but the films also manage to stray away from offering up a heavy-handed message about how humans are the real monsters. The visual style is noticeably different in three, and they all have their own specific brand of quirkiness and originality.

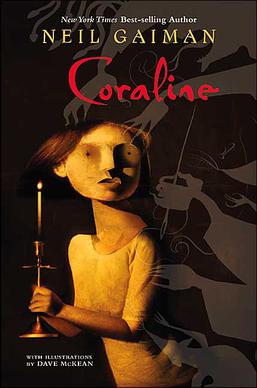

Founded in 2005 with the collapse and re-organisation of Will Vinton Studios, which was known for stop-motion content, the Portland-based company split off into two divisions: Laika Entertainment for films, and Laika House for smaller projects such as advertising. Laika began to make a name for itself in 2009 with the release of Coraline, which was nominated for an academy award for Best Animated Feature.

They're notable for some subtle efforts to feature LGBT characters in their animated family franchises (it's a small step, but it's a step) which I don't want to expand on so as not to risk spoiling parts that really should be witnessed first hand.

Also, for what it's worth, I used to dislike both this song and the band behind this one before Laika films used both in their closing credits, and I played both on a loop pretty much constantly when I was writing this piece up. If that doesn't attest to their greatness I don't know what does.

Coraline

|

| Source |

Often compared to Alice in Wonderland and occasionally mistakenly attributed to Tim Burton, Henry Selick's dark fantasy adaptation of Neil Gaiman's 2002 novel sees Coraline - a young girl who's just had to move to an isolated area with her overworked parents, who are ignoring her - long for a better, more exciting life. And a little door in her bedroom leads into what appears to be just that - an indulgent fantasy world that resembles a brighter and more entertaining version of her own home. There's only one odd thing about it: all the people in this world - replicas of her own family and friends - have black buttons for eyes. When the new world takes a turn for the sinister, Coraline must use all her wits and courage to escape.

One of the things I particularly liked about this one (besides the visuals, which we'll get to in a second) was the fact that Coraline - unlike some child protagonists - is never portrayed as unrealistically angelic. She acts the way you might expect a real kid - specifically a bored, disgruntled twelve-year-old - to act. She's occasionally a little bratty and mean-spirited, but it never gets to a point where she becomes actively unlikable. The characters we're supposed to root for aren't perfect, but their hearts are consistently in the right place.

|

| (Source) |

I feel I can't talk about this particular film without talking a little bit about its qualities as an adaptation. So in the interests of writing a more fleshed-out account, I decided to sit down and re-read the book (which I'd previously flicked through a few years ago after seeing the film.) And I realise that this next thing I'm going to say might well result in me getting my book-nerd license permanently revoked, especially considering the fact that I love Neil Gaiman, and his works tend to be in my top go-to list of books to gush about at parties. All that said, however...

...The film was better than the book.

That's not to say the book wasn't good. It's definitely worth a read in its own right, and there are a few little touches that I missed in the film. But overall, the film benefited hugely from having a visual element, and whereas Coraline's first encounter with the Other World is more explicitly sinister in the book (the Other Mother already looks a little off even without taking the button eyes into account - she's tall and thin, with claws for hands and slightly-too-sharp teeth; Coraline is evidently uncomfortable from the get-go) the creepiness and sense of not-quite-right manifest themselves more subtly and overtime in the film.

|

| Can't lie, I'd be tempted. Source |

The story transposes beautifully into a visual medium, particularly an animated one. It's easy to understand Coraline's initial desire to spend more time in the Other World (although she's still visibly apprehensive at first), since we get to experience the full impact of its beauty and escapism along with her. Just look at the garden scene, for example, or the indulgent food imagery.

It probably helps that Gaiman was heavily involved in aspects of the production and approved certain changes - such as the inclusion of Coraline's friend Wybie - being made in the film. In fact, Gaiman actually requested himself that changes be made in the film adaptation, remarking that Selick's original script was too similar to the source material. Adding an extra character was beneficial to the film if only for exposition purposes, and the added inclusion of Wybie's voiceless counterpart in the Other World adds a whole extra layer of creepiness - it's one of the early indications that something is off about the fantasy world.

The film also adds a few extended trips into the Other World, and puts Coraline's parents and their tendency to ignore her a little more into perspective (they're dealing with financial worries and approaching an important work deadline, as well as moving stress and her mother recovering from an injury.) The end product achieves something that film adaptations don't always manage: it stands up perfectly well as a film in its own right, instead of just coming off as a transposition of the book. And really, what else can you hope for?

ParaNorman

|

| Source |

The basic premise is that Norman, a young boy living in a small town that's still cashing in on an ancient witch legend, has the ability to talk to ghosts. When a centuries-old curse causes a group of long-dead puritans to rise up as zombies, Norman and his ragtag group of companions have to deal with it, and uncover a horrifying secret in the process.

This one's interesting for a few reasons. For a start, unlike the other two films which both have a very clear villain, the characters and motivations in ParaNorman are more complex. Far from being a simple juxtaposition of good vs evil, it's a lot more ambiguous as to exactly whose side you want to be on, and it never oversimplifies the ideas or talks down to its audience.

|

| The legendary witch. Source |

Norman himself is presented as a fairly ordinary, good-natured straight-man protagonist, despite his supernatural powers, although not to the point where he becomes saccharine or unrealistic, and he does have his snarky moments. Most of the humour and conflict comes from other characters acting up around him. There's something weirdly heartwarming about watching him chat to the various neighbourhood ghosts on his way to school, even if it does cause bystanders to look on with concern as what appears to them to be a boy ducking around empty space and talking to thin air.

The film's full of nice little touches, including a good few subtle visual gags that warrant at least one rewatch. There's a bit about zombies experiencing culture shock after being confronted with the modern world several hundred years after their deaths, which is legitimately hilarious.

ParaNorman might be primarily a horror-comedy, but that certainly doesn't mean it shies away from heavier subject matter. The comedy offsets a very grim backstory (but again, going to far into detail would spoil it.) Characters, dead or alive, are more complex and multifaceted to be easily divvied up into good and evil. There are strong themes of fear and bullying that are interwoven into the story.

For the record, ParaNorman was my personal favourite out of the three.

Boxtrolls

|

| (Source) |

The premise is this: the town of Cheesebridge has been misguidedly terrified for years of Boxtrolls, little underground-dwelling monsters who have (for reasons as yet unrevealed to us,) acquired a human child named Eggs who they are raising as their own, resulting in an unconventional and slightly weird but happy and loving family. The widespread fear of boxtrolls is perpetuated by Archibald Snatcher, an exterminator plotting to kill off all the creatures to gain a higher social status.

|

| Our villain du jour, Archibald Snatcher (Source) |

Although a bit of a moustache-twirler (we can tell exactly what kind of a person we're dealing with practically from his first appearance, although the other characters can't,) Snatcher has some depth as a character, and if he wasn't so horrible the audience could almost be persuaded to sympathize with his motives, especially considering how the upper class are portrayed. Like the villains in the previous two films, Snatcher's appearance and true nature are somewhat disguised, at least to the other characters; unlike the previous two, there's nothing supernatural about him. He also has the classic evil henchmen posse, which is also given a bit of an original spin, as we're given a look at antagonists who genuinely believe they're the good guys fighting the forces of evil, and increasingly question this as the story goes on. Whilst played for laughs, it's another thing you won't often see in a kids' film. And, as with ParaNorman, the town is seen rather distastefully using a past tragedy as a means for entertainment, and possibly a method of cashing in.

|

| (Source) |

No comments:

Post a Comment